Axpo UK Shaping a climate-friendly future

About Us

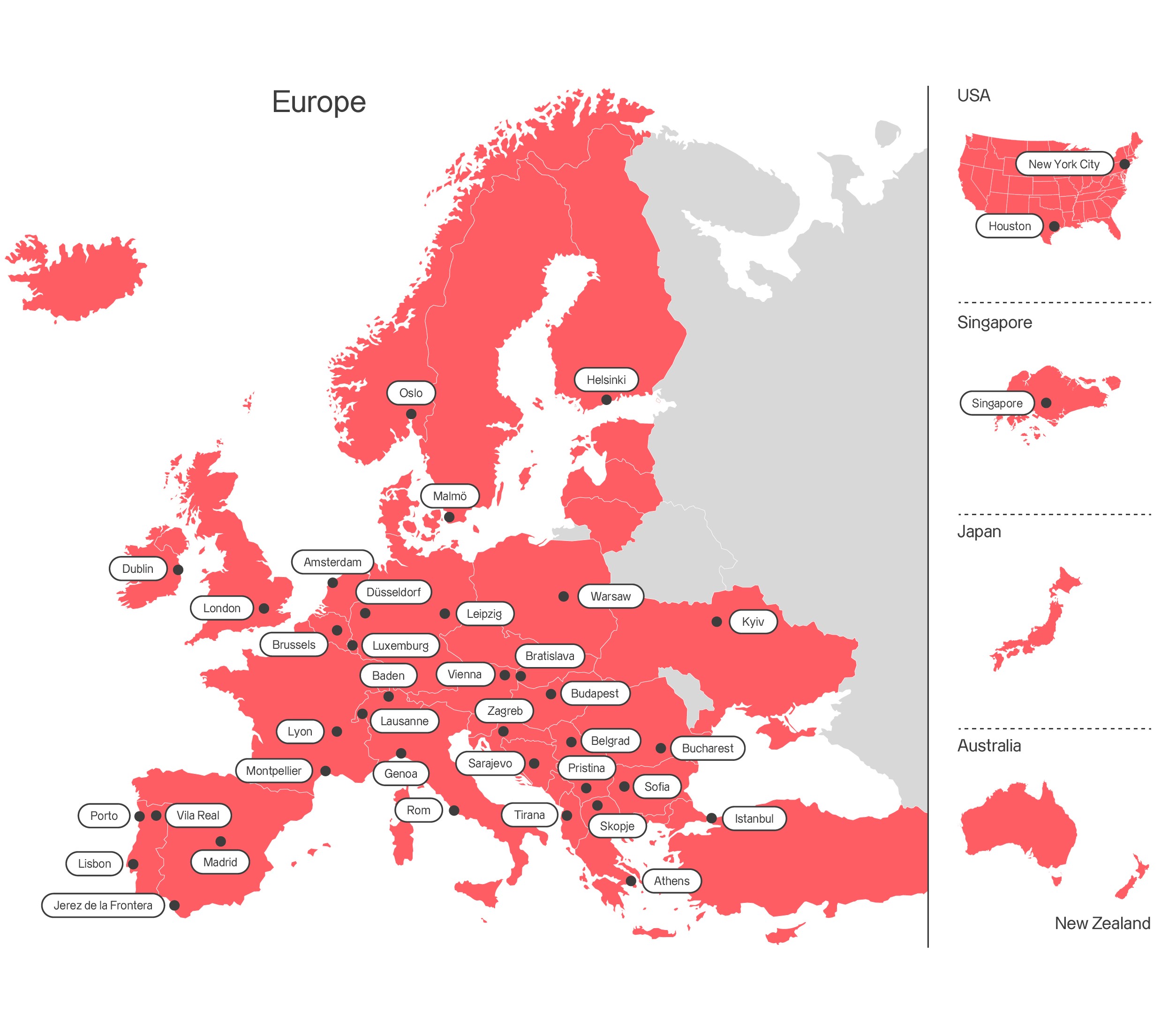

Established in 2008, Axpo UK is a leading energy supply and trading company, optimising client energy portfolios across the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Our experienced team sources electricity and gas directly from producers, manages trading through major wholesale counterparties and energy exchanges, and supplies energy to large industrial and commercial consumers. As part of the Swiss-based Axpo Group, Switzerland's largest producer of renewable energy, we contribute to the delivery of more than 40 per cent of the electricity consumed in Switzerland. Overall, the Axpo Group employs more than 7,000 people and operates in over 30 countries across Europe, North America, and Asia. Please don’t hesitate to contact us for more information.

Powering the future with global expertise and innovation

Employees

Years of experience

Countries

Energy Solutions

Axpo is driven by a single purpose – to enable a sustainable future by providing innovative energy solutions. Axpo is Switzerland's largest power producer and an international leader in energy trading and the marketing of solar and wind power. Axpo combines the experience and expertise of more than 7,000 employees who are driven by a passion for innovation, collaboration and impactful change. Using cutting-edge technologies, Axpo innovates to meet the evolving needs of its customers in over 30 countries across Europe, North America and Asia.

Power

Axpo offers a wide range of products and services tailored to meet your electricity needs. Customers benefit from Axpo's proven experience in energy optimisation, risk management and market analysis, as well as our Europe-wide presence. Your organisation’s consumption behaviour, appetite for price and quantity related risk, even the time available to spend on your project, can all influence the choice of procurement model. Axpo customers benefit from our comprehensive product portfolio, which offers both standard products and tailored energy solutions optimised to best manage your risk.

Natural gas

Natural fluctuations in energy consumption and volatile prices present market participants with major challenges. Axpo offers a wide range of products and services that can be tailored to meet your energy needs. Our customers also benefit from Axpo's proven experience in energy trading, risk management and market analysis, as well as our growing international presence. Your consumption behaviour, willingness to take risks in terms of price and quantity, and time available to devote to the project all influence the choice of procurement model. Axpo customers benefit from our comprehensive portfolio, which offers both standard products and tailored energy solutions.

PPAs

Axpo is at the forefront of the international PPA (Power Purchase Agreement) business, offering tailored PPA solutions for large consumers and generators. As the demand for 100% renewable energy increases, industrial customers are increasingly adopting this standard way of securing long-term green energy. Long-term PPAs have emerged as a crucial area to support the energy transition in the renewable energy sector. PPAs enable the development of new green electricity generation (with or without out relying on subsidies), help power the energy transition and support the fight against climate change.

Renewable energies

Axpo offers a comprehensive range of green electricity products from different renewable energy sources. With a diverse portfolio of technologies, including hydropower, biomass, biogas, wind, and solar power, we enable regional and individual renewable energy solutions for energy suppliers. We provide certificates of origin and quality labels for those technologies. With the direct marketing of renewable energies Axpo provides additional revenue, long-term investment security, and freedom from administrative and operational costs.

Market access

Axpo customers gain access to every power exchange and can trade across various maturity periods, both physical and financial, for structured options, standard products or OTC transactions. Whether an upstream producer or a participant in the mid- to downstream energy sector, customers can benefit from our strong presence across all major European power markets. Over the years we have acquired significant physical and financial risk management and trading expertise. Customers and counterparties regularly acknowledge the quality of our services in the Energy Risk Commodity Rankings.

Guarantees of origin

Organisations wishing to add environmental value to their electricity purchases can benefit from our comprehensive range of Guarantees of Origin (GOs), REGOs, ROCs and green electricity products. These cover various technologies, energy sources and labels and are all compliant with the legislation and the international European Energy Certificate System (EECS) and UK standards.

Get in touch with us

We appreciate your interest in Axpo and are here to help. Please complete the contact form and our team will respond promptly to your inquiry.

Jobs & Careers

-

Diverse career opportunities

Axpo offers more than 150 different employment profiles, providing a wide range of career paths for professionals, students, graduates, and apprentices.

-

Commitment to sustainability

Axpo employees contribute to building a sustainable future through innovative and climate-friendly energy solutions.

-

Focus on innovation

Axpo prioritises the rapid testing and validation of innovative projects, fostering a culture of progress and collaboration in the global energy sector.

Laws & Regulations

Stay informed about the legal frameworks and policies that shape our business operations. Visit our Laws and Regulations page to learn more about the standards we adhere to and our commitment to compliance and transparency.