Axpo in North Macedonia Shaping a climate-friendly future

Energy Solutions

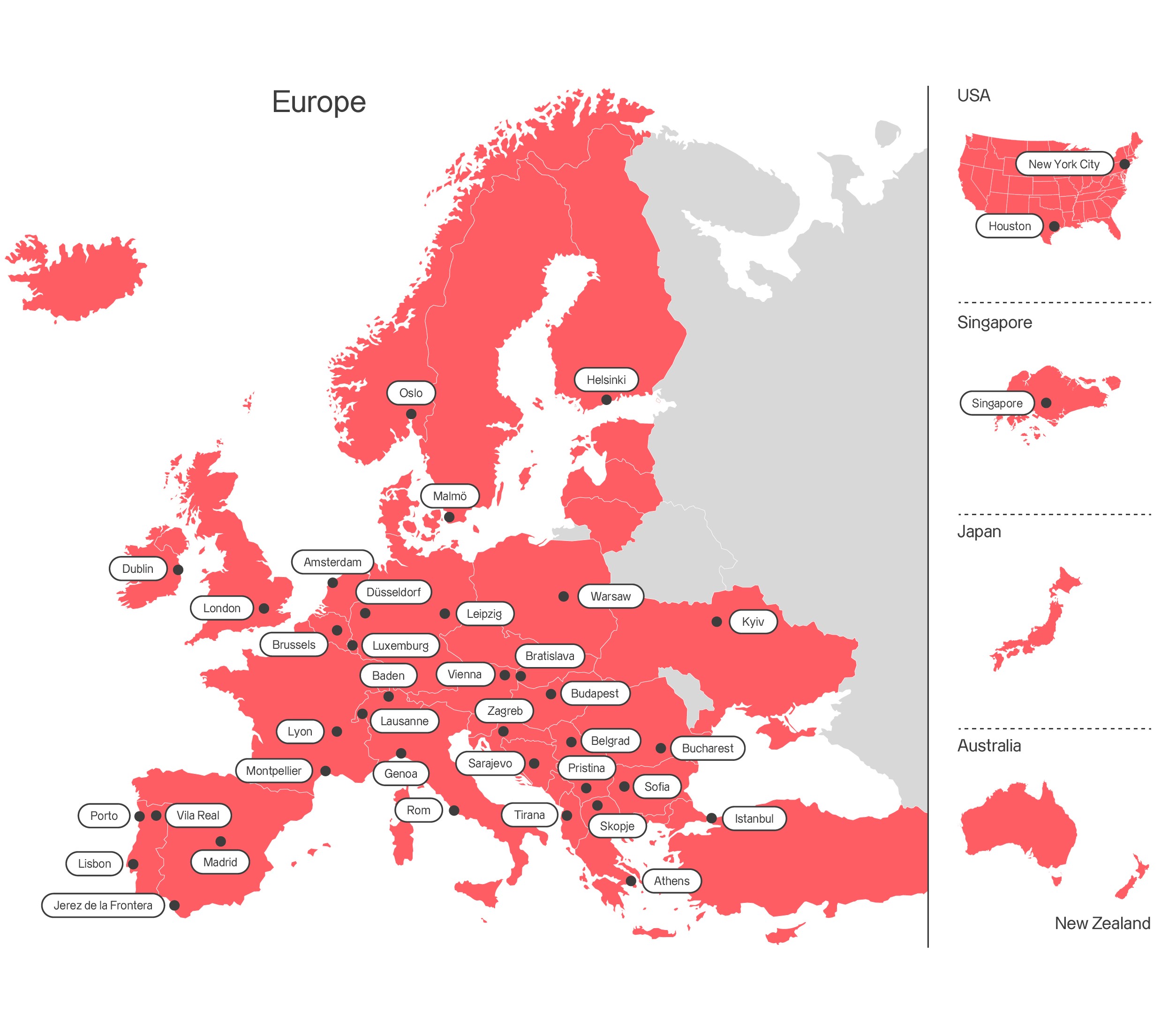

Axpo is driven by a single purpose – to enable a sustainable future by providing innovative energy solutions. Axpo is Switzerland's largest power producer and an international leader in energy trading and the marketing of solar and wind power. Axpo combines the experience and expertise of more than 7,000 employees who are driven by a passion for innovation, collaboration and impactful change. Using cutting-edge technologies, Axpo innovates to meet the evolving needs of its customers in over 30 countries across Europe, North America and Asia.

Power

Axpo offers a wide range of products and services tailored to meet your electricity needs. Customers benefit from Axpo's proven experience in energy optimisation, risk management and market analysis, as well as our Europe-wide presence. Your organisation’s consumption behaviour, appetite for price and quantity related risk, even the time available to spend on your project, can all influence the choice of procurement model. Axpo customers benefit from our comprehensive product portfolio, which offers both standard products and tailored energy solutions optimised to best manage your risk.