22.11.2023 | A certified difference

What’s behind green electricity?

Renewable electricity: many electricity providers promise it, most consumers want it. But how does the electricity from the socket come to be labelled “renewable”? It is all down to the “guarantee of origin” system. It’s an important system, but one which leaves room for improvement. While the government has initiated regulatory changes, more transparency is required.

To keep electricity flowing, the amount of power produced must equal the amount of power consumed at any given moment. Given the huge number of consumers and producers hooked up to the electricity grid, that’s a major challenge. It takes a highly sophisticated system and the combination of various international short-term and long-term markets to handle this complex task. And to make things even more complex, the market doesn’t distinguish between different environmental standards in electricity – it’s simply sold as “electricity” with no indication of whether it originated from a gas-fired power station or a solar panel. From a physical perspective, too, there’s no way to divide electrons in the electricity grid into renewable and non-renewable. So what is renewable electricity from the socket? This is where the guarantee of origin system comes in.

Guarantees of origin: an instrument for disclosing electricity quality

A guarantee of origin (GO) is a document attesting that a certain amount of electricity fed into the electricity grid (e.g. 1 kWh of solar power) is of a certain environmental quality. To declare the electricity supplied to consumers as renewable, the supplier has to be able to present GOs to the same amount. However, GOs can be traded independently of electricity. For example: a producer could sell its electricity on the exchange but transfer the guarantees of origin which relate to that electricity production separately to a supplier.

The GO is what enables the producer of renewable energy to transfer the “environmental” quality of its electricity to specific consumers. This has two effects in particular. One is that consumers can claim a certain volume of renewable electricity for themselves, allowing them to both make and fulfil pledges concerning sustainability and their products (e.g. “our products are made with 100% renewable electricity”). The other is that the GO accords renewable energies a higher market value than non-renewable energies, which represents an incentive for the expansion of renewable energies. But GOs are also used for regulatory purposes – such as when suppliers have to disclose the origin of the different elements in their electricity mix to consumers each year.

A worthwhile yet flawed system

So without GOs it would be impossible to make an assertion to consumers about the environmental quality of the electricity supplied. Ultimately, though, this is an artificial transparency which only partially reflects reality. Various changes are required to bring the transparency of the GO system closer to real-life conditions.

Firstly, there is the issue of the correlation between the time the GO arises and the time the corresponding electricity is consumed. Currently, this is determined on an annual basis. This means that to declare a unit of electricity, you can use any GO from the same calendar year. That in turn means, for example, that you can declare the electricity consumption on a dark winter’s day with a GO representing power from a PV system on a sunny summer’s day. But given the high volume of electricity imports in winter and the increase in electricity surpluses in summer, this is hardly expedient.

Secondly, the lack of an electricity agreement between Switzerland and the EU creates an inconsistency in the GO market. The Swiss GO system is linked to equivalent systems in EU countries, and this makes international trade possible. However, because there is no Switzerland-EU electricity agreement, the EU stopped recognising Swiss GOs in June 2023, which means they can’t be exported. Switzerland has not responded to date and continues to recognise EU GOs. This asymmetry on the market, along with substantial imports, reduces the value of renewable GOs domestically.

And thirdly: the system only functions when climate pledges and targets are consistently substantiated with the corresponding GOs. Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case. For example: Norway comes in for criticism because, in political terms, it presents itself as 100% renewable by pointing to its production portfolio – even though it exports the lion’s share of its GOs rather than using them to disclose electricity origin domestically (only 30% of consumption is declared with renewable GOs). The exported GOs then end up in countries like Switzerland, where electricity is declared renewable on the consumer side.

Regulatory developments and further areas for improvement

The government has initiated various improvements to the GO system. In September 2022, parliament tasked the Federal Council with reducing the correlation period between consumption and production in electricity disclosure. The Federal Council responded by introducing an amendment to the relevant ordinance by which, starting in 2026, electricity consumption within a given quarter can only be declared with GOs within the same quarter. And this correlation period could be shortened further, resulting in higher administrative costs (particularly in the case of weekly, daily or even quarter-hourly labelling).

In addition, by passing the “consolidation bill”, parliament has decided that the standard electricity product should in future consist “primarily” of domestic renewable energy sources. The basis for proof is the Swiss GO. This change is likely to boost production of domestic renewable electricity but it doesn’t solve the structural problem in the GO market (asymmetry with the EU and high export quotas for some countries).

In essence, international trade with GOs is desirable and reasonable – much like the international electricity market. However, resolving the asymmetry in the GO market will require an electricity agreement – or temporary adoption of an exclusively domestic system. But even with an electricity agreement, the GO system requires improvement on the EU side (e.g. quarterly electricity disclosure), or renewable targets for individual countries need to be consistently aligned with their declared electricity consumption.

For Switzerland, the most sustainable solution is probably the quality at the heart of the GO system: transparency. Consumers, for instance, would benefit from greater visibility around the environmental and, above all, geographic dimension of their electricity mix. One way of achieving this would be to modernise the tables that regulatory authorities use for communicating the electricity mix. But ultimately, an even more effective approach would be complete market liberalisation, which would give the consumer additional control over their electricity products and thus lead to a greater diversity of products and greater transparency.

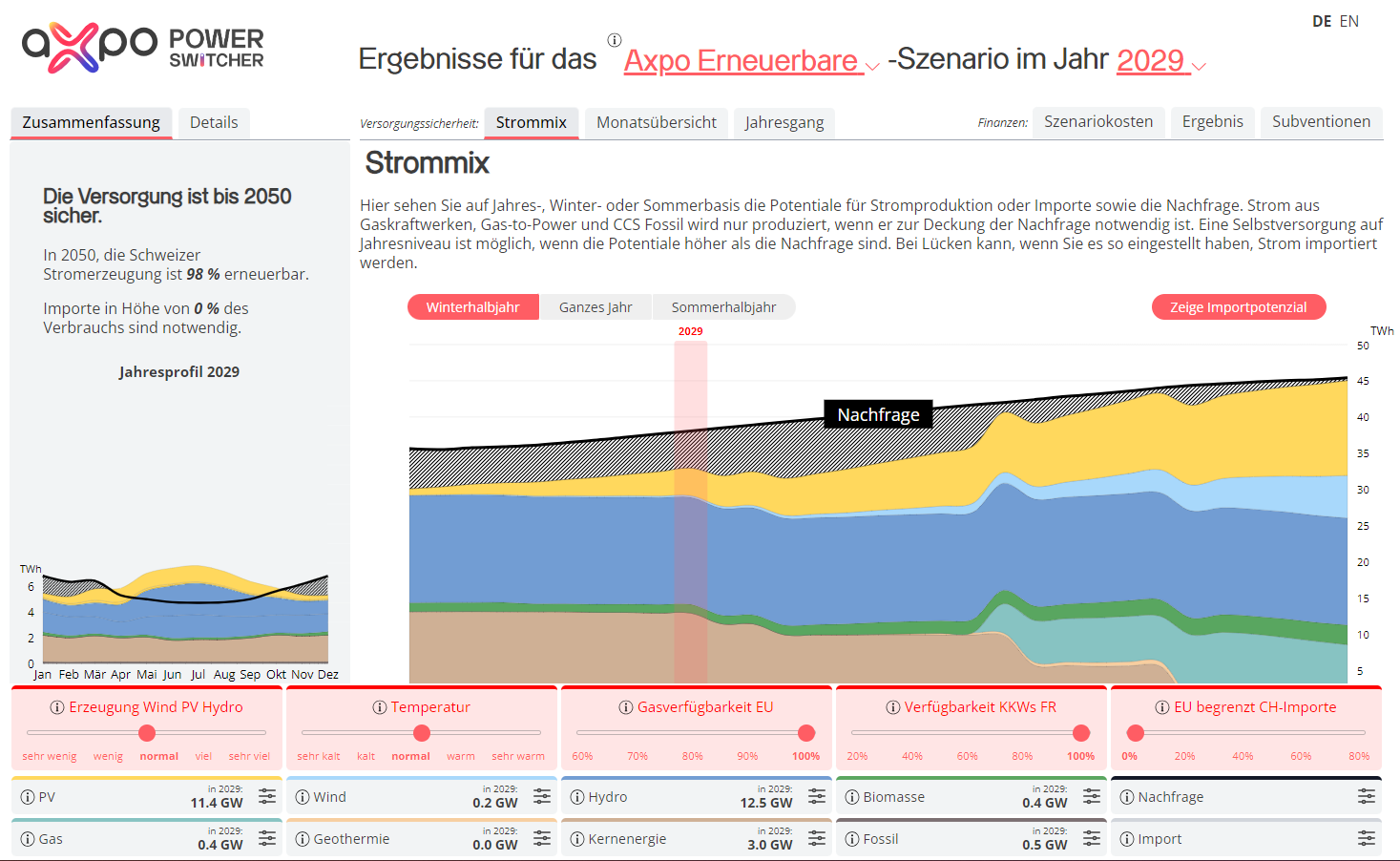

Switzerland’s electricity mix

According to official statistics on guarantees of origin from 2022, the electricity that comes out of Swiss sockets is made up of 65% hydropower, 19.6% nuclear power, 13.7% renewables (solar, wind, biomass, etc.) and just 1.9% fossil energy sources. Around 20% of electricity consumption (or one third of hydropower) is declared with foreign hydropower GOs, from countries such as Norway, France and Sweden.

A simplified example

The function of a GO can be illustrated with a simplified example. Let’s say there is an electricity system with two producers, a gas-fired power station and a hydropower power station, each of which produces 50 MWh per year, and two consumers who each consume 50 MWh. When electricity is traded in uniform quality – or from a physical perspective – both consumers receive the same electricity mix from the grid, which is 50% renewable and 50% fossil. If GOs are used to disclose the “environmental” quality of the hydropower plant, these can be allotted to specific consumers. This means one consumer could purchase the GO from the hydropower plant and then declare their electricity consumption as renewable. The other consumer would then be drawing down fossil-based electricity.

.jpg)